- ~36 – 30 million years before present – The Suwannee Limestone stratum of the Upper Floridan Aquifer is formed from marine deposits in a shallow sea which inundated all of Florida.

- ~25 – 20 million years before present – The limestones of the St. Marks Formation are deposited above the Suwannee Limestone.

- ~20 million years ago – present – During periods of lower sea level, Wakulla Spring forms from dissolution of the St. Marks Formation and intersects the aquifer in the underlying Suwannee Limestone.

- ~10 million – 10,000 years before present – Pleistocene megafauna, including mastodon, wooly mammoth, short-faced bear, giant ground sloth, saber-tooth tiger, and giant armadillo, inhabit the Wakulla Spring area.

- 120,000 years before present – Wakulla Spring is once again inundated by higher sea levels.

- ~14,500 years before present – The first humans inhabit the Wakulla Spring area.

- 1818 – In his “Topographical Memoir,” Captain Hugh Young reports that the source of the “Wakally” River is “a rocky spring, 60 feet in diameter and 120 feet deep, with water so transparent that objects on the bottom could be clearly seen.” He describes a “sedge grass” that choked the river. (Revels, 2002)

- 1823 – John Lee Williams notes “squadrons of fish” in the spring (Revels, 2002).

- 1833 – Charles Latrobe, author of “The Rambler in North America,” describes Wakulla Spring as “a large circular basin of great depth, in which the water appears to be boiling up from a fathomless abyss, as colorless as the air itself.” (Revels, 2002).

- 1835 – An anonymous author reports in “Letters on Florida” that the origin of Wakulla Spring “is said to be Lake Jackson.” They describe the spring as being “so still and of such perfect transparency, that the smallest object is seen at the immense depth of water below; and the spectator upon its surface, sits and shudders as if suspended in empty air.” (Revels, 2002).

- 1837 – French naturalist Francis de La Port, Comte de Castelnau, in his “Essay on Middle Florida 1837-1838,” describes wildlife he encountered on a journey up to the spring from St. Marks in 1837: “beautiful herons of a dazzling white, pelicans with huge beaks provided with a big pocket . . . numerous long-legged water fowl, the pretty Carolina parakeet.” He also remarks on the “vast cypress groves whose trees are grouped in the form of islands; everywhere fallen tree trunks blocked our way.” He also repeats the hypothesis that “it probably has an underground connection with Lake Jackson.”

- 1855 – E.S. Gaillard describes the spring as being “the color of a paling sapphire” which he attributes to “sulphuret of lime being held in suspension.” (Revels, 2002)

- 1876 – Sidney Lanier, in his guidebook, “Florida: Its Scenery, Climate, and History,” describes the spring’s waters as “thrillingly transparent” with a “mosaic of many-shaded green hues.” (Revels, 2002)

- 1882 – Artist Frank Taylor declares Wakulla is “’more interesting than Silver Spring’ due to its greater depth and large alligator population.” (Revels, 2002)

- 1925 – Herbert Stoddard reports on his first visit that the river was “comparatively barren of bird life” with “probably not more than 2 or 3 pairs of limpkins in the area” (Memoirs of a Naturalist 1969). Stoddard continues: “About that time…the state game commissioner closed to fishing a three-mile stretch below the springs” and “the owners of lands adjoining the river posted the lands against hunting, and the result was a sanctuary for both fish and birds”.

- ~1931 – Owner George T. Christie begins operating glass-bottom boats. (Revels, 2002)

- 1934 – Edward Ball purchases springs and surrounding property.

- 1935 – Edward Ball constructs the sand beach. (Revels, 2002)

- 1941 – Edward Ball erects the river fence just above the Shadeville Road bridge.

- 1945 – 1946 – Letters from Wakulla Spring property managers to Edward Ball mention tannic dark conditions in summer 1945 and the first three months of 1946. (Revels, 2002)

- 1946 – First Christmas bird count.

- 1952 – Greis and Yentsch of the FSU Oceanography Institute record a Secchi disc visibility depth of 22 meters (73 feet) after 6 weeks of no rain (Kowalkowski, 2010).

- 1955 – 1957 – A group of FSU students and Stanley Olsen of the Florida Geological Survey, conduct 450 dives and penetrate to 750 – 1,100 feet from the entrance and to a depth of 250 feet.

- 1960s – Edward Ball allows recreational spring diving for 3 – 4 years. Based on radiocarbon dating, hydrologist Larry Brill estimates that the spring’s source is no more than 60-70 miles away. He also observes that its level fluctuates in response to changes in atmospheric pressure as well as rainfall and the tides. (Burgess, 1989)

- 1962 – A letter from the Wakulla Spring property manager to Edward Ball mention tannic dark conditions in April. (Revels, 2002)

- 1963 – Edward Balls leases his Wakulla property to the National Audubon Society which establishes an official bird sanctuary and hires a full-time game warden. (Revels, 2002)

- 1965 – In September, dark water due to tannins associated with heavy rain limit filming for “Around the World Under the Sea.” (Revels, 2002)

- 1966 – Old Joe, the largest alligator on the spring, is shot by a poacher on the night of July 31.

- 1967 – The National Park Service recognizes Wakulla Springs as a Registered National Natural Landmark.

- 1968 – 69 – Edward Ball dredges tour boat channels, including the Sally Ward spring run, and deploys the current river tour boats. The National Audubon Society withdraws its sponsorship of the sanctuary. (Revels, 2002)

- 1969 – Florida State University Geography Department authors of “Tour Guide of the New Coastal Plain South of Tallahassee” report that “Wakulla Springs is one of the few places where the limpkin still nests.” (Revels, 2002)

- Early 1970s – The limpkin population begins to increase. (Revels, 2002)

- 1973 – Tom Morrill and Jack Rudloe file a lawsuit challenging the fence and the cutting of cypress to create the “Back Jungle” channel for tour boats. The case was dismissed multiple times by the Wakulla County Circuit Court as were subsequent appeals all the way to the Florida Supreme Court. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers initially declared the upper river navigable and subject to regulation, but subsequently reversed. (Revels, 2002) The fence remains in place at the southern boundary of the park.

- 1981 – Using propulsion vehicles and stage diving techniques Paul DeLoach, Mary Ellen Eckhoff, and John Zumrick conduct 2 dives in Wakulla Spring cave and reaching 1100 feet and a depth of 260 feet.

- 1981 – 83 – The same divers enter Sally Ward Spring three times and penetrate 1,192 feet to a depth of 260 feet.

- 1986 – The Northwest Florida Water Management District, Florida Department of Natural Resources, and the Nature Conservancy purchase the Edward Ball property from the Nemours Foundation for a State Park for $7.15 million. The property is subsequently conveyed to the State of Florida. The park opens October 1.

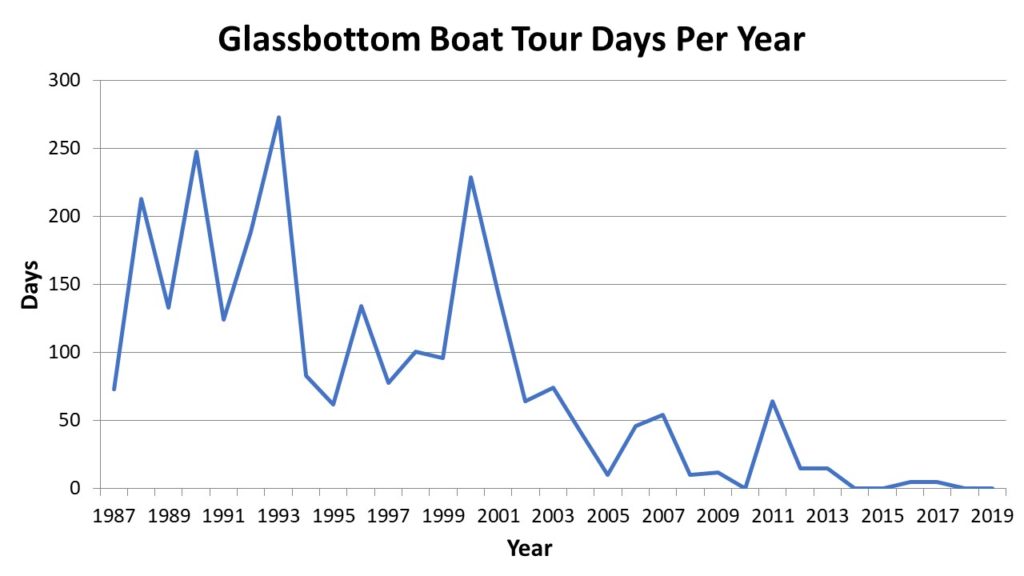

- 1987-1992 – Glass-bottom boat tour days per year vary widely from a low of 73 in 1987 to a high of 248 in 1990.

- 1987 – The State Department of Natural Resources designates the Wakulla River as an Outstanding Florida Water. The U.S. Deep Caving Team on the Wakulla I expedition maps 2.3 miles of tunnels in the Wakulla cave at depths averaging 260-320 feet with a maximum penetration of 4,176 feet. The team also maps the Sally Ward cave for a total tunnel length of 1,530 feet and a maximum depth of 289 feet. Using dye and radioactive isotopes the team demonstrates links between Indian Spring, Sally Ward Spring, and the main Wakulla tunnel. Diver collect blind albino catfish 4,000 feet from the cave entrance at depths between 200 and 300 feet. (Revels, 2002)

- 1989 – Jim Stevenson, then Director of the Department of Natural Resources Office of Resource Management, coordinates the first full-river wildlife survey from the spring to the river’s confluence with the St. Marks River.

- 1992 – Jim Stevenson convenes the Wakulla Springs Water Quality Working Group to investigate recent declines in glass-bottom boat tours. In September, park staff begin surveying wildlife along the river boat tour route every month (Min.Wak Sprng WQ Wkg Grp.04-16-92).

- 1993 – The State Division of Parks issues first research diving permit to the WKPP (Woodville Karst Plain Project). Glass-bottom boats are operated for 273 days, the most during the history of the park.

- 1994 – Wakulla County adopts the Wakulla Springs Special Planning Area. The Park installs a new sewage collection and treatment system replacing two septic tanks close to the river (Revels, 2002). High water from several months of above-average rainfall (March – October) including tropical storm Beryl – drowns apple snail eggs leading to precipitous loss of the primary food source for limpkins. Glass-bottom boat tours decline to 83 days.

- 1995 – Glass-bottom boats are only operated for 62 days; the fewest since the park’s opening.

- 1995 – 1996 – Average annual mean limpkin counts drop from 9 in 1994 to 2 in 1996.

- 1996 – The Friends of Wakulla Springs is founded as the official Community Support Organization for Wakulla Springs State Park to prevent construction of a service station on the Kirton property at the corner of Wakulla Springs Road and Bloxham Cutoff. Lakewatch volunteers initiate water sampling of the spring.

- 1997 – Park staff discover the invasive plant hydrilla by the boat dock and initiate hand removal. By December hydrilla extends one quarter mile downriver to first turn. First recorded small group of manatee arrives in August. Florida State University faculty Rodney DeHan and David Loper found the Hydrogeology Consortium, the predecessor to the Wakulla Springs Alliance, to address problems of water flow and contaminant transport in karstic aquifers.

- 1998 – Hydrilla invades the swimming area and spring basin and continues to expand down river. Park continues hand pulling and applies Aquathol granular herbicide in swimming area without success. The Florida Geological Survey convenes the Wakulla Springs Woodville Karst Plain Symposium. U.S. Deep Caving Team conducts Wakulla II dive expedition extending mapped passages and producing 3-D maps of the passages. Wakulla County expands the Wakulla Springs Special Planning Area to encompass the entire spring basin within the county.

- 1999 – Hydrilla extends past first turn and begins to occupy large areas of the main channel. Park starts contract mechanical removal. Cherokee Sink property (approximately 1,800 acres) plus an additional 1,200 acres are added to the park. The Florida Attorney General’s Office files an eminent domain claim on the Kirton property setting the stage for ending a six-year effort by Kirton to develop the property. Total wildlife abundance along the river boat tour route peaks at an annual mean of 742 animals counted per monthly survey, driven in part by a surge in American wigeon with survey counts of 700-800 in December 1999 and January 2000.

- 2000 – The Florida Springs Task Force published “Florida’s Springs: Strategies for Protection & Restoration” report. Hydrilla invasion extends beyond tour boat turnaround. Park begins all-route mechanical removal of hydrilla. Average annual mean limpkin count drops to zero. Glass-bottom boat tours peak for the last time at 229 days. A single manatee is observed in November.

- 2001 – The State Division of Recreation and Parks publishes updated Unit Management Plan for Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park.

- 2002 – The State Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Invasive Plant Management, conducts first Aquathol drip treatment in April followed by second treatment in November. Initial treatment kills back 70 to 80 percent of hydrilla stems, but roots remain in sediment. Native submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) species also are harmed to varying degrees. The initial hydrilla die-off results in a surge of flow that scours the upper river bottom resulting in additional native SAV loss and opening the shallows at the Shadeville Road bridge. A large crayfish die-off occurs after the first treatment. The River Sinks property (approximately 1,300 acres) is added to the park.

- 2003 – 2004 – Total wildlife abundance declines following successful herbicide control of hydrilla. Annual mean animal counts per survey drop to 240-250 from the 1999 peak of 742.

- 2003 – The first group of manatee (eight) arrives in August, likely due to enhanced access resulting from the hydrilla die-off surge in flow. (Since 1997 only occasional individuals had been observed.) Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues.

- 2004 – Part staff initiate restoration of eel grass, aka tape grass (Vallisneria americana), transplanted from the lower river outside of the park to the spring basin and the area near the boat docks to try to offset collateral damage to native submerged aquatic vegetation from the herbicide treatments. DEP biologist Jess Van Dyke releases 490 half-grown apple snails into upper river, in an effort to restore the principal food of the limpkin. Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues.

- 2004 – 2005 – Dye trace studies by Hazlett-Kincaid Inc. connect the Munson Slough swallet, Ames Sink, to Indian Springs in 17 to 20 days and on to Wakulla Spring three to five days later (22-23 days total).

- 2005 – Nine manatee are observed at the spring in April. Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues. A State Department of Environmental Protection study of Aquathol crayfish toxicity finds that the die-off after the initial herbicide treatment in 2002 may have been caused by dissolved oxygen depletion from decomposing hydrilla rather than a direct toxic effect. Jess Van Dyke releases 1,500 more apple snails. The Alliance’s predecessor, the Hydrogeology Consortium, along with local governments, the Northwest Florida Water Management District, several state agencies, and 1000 Friends of Florida, sponsor a workshop “Solving Water Pollution Problems in the Wakulla Springshed of North Florida.” At that workshop, Park Biologist Scott Savery describes a yoyo effect of the herbicide treatment: “[A[fter the herbicide treatment there is much less vegetation and algae covers most everything in the water. As the system recovers, the natives (pondweed, naiad, spring tape, and tape grass) grow back faster than the hydrilla, but over time [6-8 months] the hydrilla grows back and overtakes the natives.” Glass-bottom boats operate for only 10 days; the fewest since the park opened.

- 2006 – Dye trace studies by Hazlett-Kincaid Inc. demonstrate connection between the City of Tallahassee treated wastewater spray field on Tram Road and Wakulla Spring with a travel time of 56 days. In March, the Florida Wildlife Federation, Manley Fuller, Joseph Glisson, Wakulla County, and the Florida Attorney General’s Office contest the operating permit issued by the State Department of Environmental Protection to the City of Tallahassee for its wastewater treatment facilities and spray field, arguing that the permit does not adequately protect the water quality of Wakulla Springs. In December the City and petitioners reach a settlement agreement stipulating measures for the city to take to enhance its wastewater treatment so as to reduce the nitrogen concentration in its treated effluent to no more than 3.0 mg/L. Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues. Algae, including the so-called blue-green alga, Lyngbya, begin to dominate the SAV of the spring basin and upper river, forming dense mats. [Blue-green algae are bacteria known as cyanobacteria rather than true algae.] Total wildlife abundance rebounds partially to an annual mean total animal count per survey of 389 with especially high counts of American coot, American wigeon, white ibis, and common gallinule. Wakulla County adopts regulations that increase setbacks from sinkholes and springs and require performance-based septic systems for new developments and as replacements for older, malfunctioning systems.

- 2007 – Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues as do eel grass transplanting project and apple snail releases. In July, WKKP divers link Leon Sinks and the Wakulla cave systems establishing the 4th longest cave in world (1-3 in Yucatan, Mexico) totaling 32 miles and 25 entrances. In December, WKKP divers traverse from Turner Sink to Wakulla Springs, covering 6.8 miles. A manatee baby (Gail) is born in Sally Ward Spring run in July. Leon County establishes the Primary Springs Protection Zone in the southern area of the county where soils are more permeable and pollutants on or near the land surface are more likely to find their way into the Floridan aquifer that feeds Wakulla Spring. Advanced Geospatial Inc completes Leon County Aquifer Vulnerability Assessment. State Division of Recreation and Parks publishes updated Unit Management Plan for Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park.

- 2007-2008 – Manatees spend the winter in the park for the first time (peak number 12).

- 2008 – The State Department of Environmental Protection designates the upper Wakulla River as a biologically impaired waterbody because of excessive algal mats attributed to excessive levels of nitrate-nitrogen from anthropogenic sources. Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues followed by a second crayfish kill of lesser magnitude (several hundred). Eel grass transplanting continues. August 22-25 heavy rains from tropical storm Fay (11.5 inches in park) raise the river stage to 4.4 feet and generate a record flow of 2,330 cfs recorded at the USGS gauge at the Shadeville Road bridge (22% higher than all-time previous record in 1973).

- 2009 – Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues. Total wildlife abundance dips to 197 annual mean total animal counts per survey. Advanced Geospatial Inc completes Wakulla County Aquifer Vulnerability Assessment.

- 2009 – 2011 – Modifications to the City of Tallahassee’s T.P. Smith wastewater treatment plant result in a 33 percent reduction in the nitrogen concentration of treated effluent applied to the Tram Road spray field.

- 2010 – 32 manatees are observed in January in the spring and river; a new record. Aquathol treatment of hydrilla continues. Summer apple snail egg clutch survey counts 2,158, a new record following the reintroduction effort. The Wakulla Spring Basin Working Group conducts a “Future Scenarios Visioning” exercise for the Year 2035 with approximately 40 stakeholders. Participants envision both a best-case scenario at Wakulla Spring thatthey termed “The Crystal Bowl of Light” and a worst-case scenario termed “The Black Lagoon.”

- 2011 – WKPP reports that explored connected cave length from Leon Sinks Cave System to Wakulla Spring is 31.9 miles. Spot treatments of granular Aquathol are applied to hydrilla in May and August; no full river treatment. New record count of apple-snail egg clutches surveyed: 2,519. Glass-bottom boat tours are operated for 64 days; the most since 2003. Lombardo Associates, Inc. completes its “Onsite Sewage Treatment and Disposal and Management Options for Wakulla Springs” report for Leon and Wakulla Counties and the City of Tallahassee.

- 2011 – 2013 – During the winter of 2011-2012 manatee are present in high numbers in and around the spring, with a high count of 51. A single limpkin is observed regularly along the river boat tour route between November 2011 and May 2012; the first residency since April 2000. Individuals are seen intermittently during the rest of 2012 and through August of 2013. Further enhancements to the City of Tallahassee’s T.P. Smith wastewater treatment facility result in an additional 75 percent reduction in treated effluent nitrogen concentration by December 2013, achieving the settlement agreement standard of 3.0 mg/L by October 2012.

- 2012 – State Department of Environmental Protection publishes a total maximum daily load (TMDL) standard for the upper Wakulla River: monthly average of 0.35 mg/L nitrate-nitrogen. Low-volume liquid Aquathol treatment for hydrilla. Glass bottom boats are run for 14 days. June 25-27 tropical storm Debby raises Wakulla River height 3.2 feet to 4.9 feet. The Northwest Florida Water Management District measures flow at the spring of 2,190 cubic feet per second (more than 1.4 billion gallons per day) on June 27. The flooding washes away apple-snail eggs, resulting in a yearly total of only 715 clusters, down from 2011’s 2,519 clusters. In November, park staff member Bob Thompson expands river boat tour wildlife survey to weekly with volunteers. The Hydrogeology Consortium changes its name to Wakulla Springs Alliance.

- 2012 – 2013 – Glass-bottom boat tours decline to 15 days for two years in a row after which they occur from zero to 5 days per year through 2019.

- 2013 – State Department of Environmental Protection initiates development of a Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) for the Upper Wakulla River and Wakulla Springs Basin to reduce nitrate-nitrogen levels in the river to the TMDL monthly average standard of 0.35 mg/L. Hydrilla fails to recover from winter grazing by manatee; no Aquathol treatment. Park staff and volunteers begin quarterly surveys of submerged aquatic vegetation along seven transects in the spring and upper river.

- 2013 – 2018 – Total wildlife abundance declines again after attaining a third peak of 297 annual mean total animal counts per survey in 2012, then flattens out with annual mean counts ranging from 167 to 223. Three species continue previous declining trends (common gallinule, wood duck, and osprey), and one begins to decline (great blue heron), but seven species exhibit increasing trends (American alligator, anhinga, double-crested cormorant, great egret, hooded merganser, pied-billed grebe, and yellow-crowned night-heron).

- 2014 – No further herbicide treatment of hydrilla is necessary in this and subsequent years. Nitrate-nitrogen concentrations at the spring level off at approximately 0.40 mg/L, down from a high of 1.00 mg/L in 2001. City of Tallahassee treated effluent averages 1.4 mg/L nitrate-nitrogen. Northwest Florida Water Management District begins minimum flows and levels study for Wakulla and Sally Ward Springs; completion scheduled for 2020.

- 2015 – Manatee numbers decline and level off following the demise of the hydrilla. State Department of Environmental Protection publishes first Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) for the Upper Wakulla River and Wakulla Springs Basin setting forth an initial five-year strategy to reduce anthropogenic nitrate-nitrogen loadings to the spring. Wakulla County begins projects to extend sewer to the Magnolia Gardens and Wakulla Gardens subdivisions within the Wakulla Spring Priority Focus Area.

- 2016 – Seán McGlynn (McGlynn Laboratories, Inc.) completes a project for the Wakulla Springs Alliance to estimate nitrogen discharges to the Upper Floridan Aquifer from sinking streams and sinking lakes in the Wakulla springshed.

- 2017 – The City of Tallahassee initiates its Sewer Over Septic program targeted at 130 septic tanks in the Wakulla Springs Priority Focus Area in neighborhoods were sewers are already available. Leon County begins its Advanced Septic System Pilot Project to upgrade septic systems outside of septic-to-sewer project areas. Eric Flagg (Jellyfish Smack Productions) completes “Following the Water to Wakulla Spring” video for the Wakulla Springs Alliance.

- 2018 – The State Department of Environmental Protection publishes revised Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) for the Upper Wakulla River and Wakulla Spring Basin calling for a total load reduction at the spring vent of 139,564 pounds of nitrogen per year by 2033. Leon County begins septic-to-sewer conversions for up to 600 septic systems in four areas within the Wakulla Spring Priority Focus Area. The State Department of Environmental Protection designates Wakulla Spring as a State Geological Site.

- 2019 – The State of Florida purchases the 720-acre Ferrell tract. The so-called bulrush island at the tour boat turnaround begins to disintegrate for reasons yet-to-be-determined. Leon County begins design and permitting for the Woodville septic-to-sewer conversion project to be completed by 2024. Leon County also initiates a Comprehensive Wastewater Treatment Facilities Plan to evaluate wastewater management alternatives to traditional septic systems, also known as onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS) in order to reduce nitrogen discharges to groundwater. Wakulla County begins a comparable Wastewater Treatment Facilities Assessment project. The Wakulla Springs Alliance publishes the final report for its Phase I study of the causes and sources of dark water at Wakulla Spring, completed by McGlynn Laboratories, Inc.

- 2020 – The COVID-19 pandemic leads to closing of Wakulla Springs State Park in March; park staff operate one tour boat per day to maintain channel and wildlife adaptation to boat traffic. The park opens for some activities in May with limited river boat tour seating to maintain social distancing. Loss of bulrushes and accompanying erosion of the marsh island at the tour boat turn around continues. Salinity spikes associated with Spring Creek flow reversals are the suspected cause. Wakulla County announces plans to dispose of treated wastewater from the upgraded Otter Creek wastewater treatment plant via a rapid infiltration basin located on the former Moore property parcel located within the Wakulla Sprmgs BMAP Primary Focus Area. WSA raises concerns with the resulting increase in nitrogen discharges to the Wakulla Springs aquifer.

- 2021 – In May 2021, park staff and volunteers observe die-offs of three species of emergent vegetation along the tour boat route: knotweed (Polygonum sp.), water hemlock (Cicuta maculatum), and pickerel weed (Pontederia chordata). This is important habitat for common gallinule, pied-billed grebe, and least bittern. Park staff and volunteers find evidence of distress to those species along the entire three miles of the river within the park as well as downstream of the park boundary but not in other nearby streams, No cause is ever determined. By September, surviving plants begin to bounce back, but by that time the river has lost about 20,000 square feet (0.4 acre) of emergent marsh habitat along the upper mile. A dye test conducted by the Woodville Karst Plain Project establishes a connection between the Chip’s Hole Cave System and the Wakulla-Leon Sinks Cave System. WSA, joined by Big Bend Sierra Club, 1000 Friends of Florida, and Florida Wildlife Federation, urges Wakulla County to select an alternative site for Otter Creek treated wastewater disposal that is outside the Wakulla Springs Primary Focus Area. WSA joins Clean Water Wakulla to urge Wakulla County to assess the Wildwood Golf Course as an alternative site where further nitrogen removal can be accomplished through irrigation of the golf course. Wakulla County’s consultant, Dewberry, prepares a master plan for county acquisition and management of the Wildwood Golf Course, rebranded as the Wakulla Sands Golf Course, including use of treated wastewater for irrigation.

- 2022 – A second, smaller scale, die off of emergent vegetation occurs in May. followed by a precipitous decline in pied-bill grebe numbers. Meanwhile counts of white ibis and hooded merganser, which compete with pied-billed grebes for crayfish, increase steadily. Southwest Georgia Oil Company applies to Wakulla County. for a comprehensive plan amendment and zoning change that would allow the construction of a mega-gas station above the Chip’s Hole cave system that leads directly to Wakulla Springs. WSA attempts unsuccessfully to convince the City of Tallahassee to persuade the Origis Company, which manages the solar farm at the city airport from which the city purchase electric power, to employ sheep grazing in lieu of herbicides to control vegetation.

- 2023 – Annual mean counts per survey of pied-billed grebes drop to 3, from 18 in 2021 and 32 in 2018. Over 2,000 emails are sent to Wakulla County commissioners by Springs Advocates through Florida Springs Council’s system and by partnering groups across the state like Sierra Club Florida, Progress Florida, Florida Wildlife Federation, the Downriver Project (Clean Water Wakulla), and the Wakulla Springs Alliance. Southwest Georgia Oil withdraws the application putting the project on hold. Divers with the Woodville Karst Plain Project discover the long-sought connection between the Chip’s Hole Cave System and the Wakulla-Leon Sinks Cave System.

- 2024 – Through the efforts of State Representative Jason Shoaf and State Senator Corey Booker, $3.8 million is appropriated in the 2024-25 state budget for Conservation Florida to acquire 225 acres of property owned by St. Joe Corporation that includes Chips Hole and the underlying cave system, plus land south of the Southwest Georgia Oil property to be swapped for that property thereby moving the planned gas station further away from the cave system. Wakulla Sands Golf Course opens applying up to 1 million gallons per day of treated effluent from the Otter Creek wastewater treatment facility.

- 2025 – Only scattered remnants of he bulrush island at the tour boat turnaround remain.

Timeline built upon one prepared by Dana Bryan for 1925-2014, supplemented by information from Robert F. Burgess’s The Cave Divers (Dodd & Mead, 1989), Zoe Kulakowski’s Chromphoric Dissolved Organic Carbon Loading of Five Intermittent Streams Recharging Wakulla Springs, Florida (2010), Tracy J. Revels’s Watery Eden: A History of Wakulla Springs (Friends of Wakulla Springs State Park, 2002), Wakulla Spring Restoration Plan (Florida Springs Institute, 2014), and other sources.